How we built automatic clustering for LLM traces

Contents

We're all used to traditional clickstream product analytics data. It's often one of the most important datasets for anyone trying to build something. We're also familiar with backend observability data — metrics, logs, traces — more operational, but still essential.

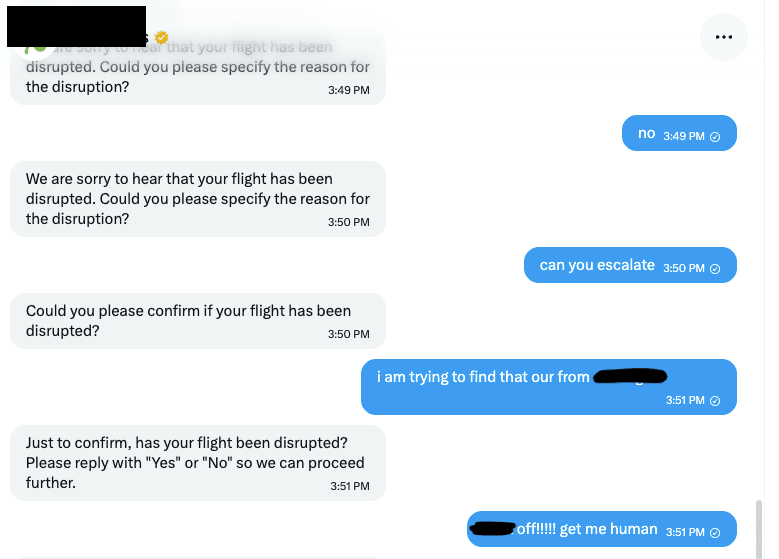

In the age of AI, though, we now have a different kind of data that combines and mashes aspects of both together. I'm talking about the LLM traces and generations your AI agent or agentic workflows produce as they get stuff done.

This data is crucial for seeing whether your agent is actually doing its job, and it's also rich with insights about how your users are using it, what they're trying to do, and even how they feel about the whole interaction.

Think about all your interactions with an AI in the last week and all the subtle (or not so subtle) signals embedded in them. There's a lot of useful information there for the people building the thing you're using — and it all kind of comes for free by the nature of the UX.

So with this in mind, we built a new feature recently, aptly named "Clustering." We probably should have called it "Agentic AI-driven magic AI unicorn insights agentic" but I'm bad at names.

Here's how the whole pipeline works under the hood, with links to the code if you want to dig deeper. If you just want to see it in action, skip to the demo.

The pipeline

Here's the overall flow from raw traces to clustered insights:

- Ingest — Traces and generations land as PostHog events

- Text representation — Convert each trace to a readable text format

- Sample — Hourly sampling of N traces/generations

- Summarize — LLM-powered structured summarization

- Embed — Generate embedding vectors from summaries

- Cluster — UMAP dimensionality reduction + HDBSCAN clustering

- Label — An AI agent names and describes each cluster

- Display — Clusters tab with scatter plot and distribution chart

Design considerations

Before diving into the steps, here are the main considerations we kept coming back to and the choices we made for each:

- Huge traces — Some traces are enormous and can't just be thrown at an LLM. Our answer: the uniform downsampling described in step 1. We iteratively drop lines while preserving the overall structure, so even massive traces fit within context limits.

- Keeping costs sane — Running LLMs on every single trace would bankrupt us. So we sample a small random subset each hour, use GPT-4.1 nano for summarization (fast and cheap), and are planning to move to the OpenAI Batch API to optimize further.

- One-size-fits-all vs. custom summaries — It's hard to have a single general summary schema that works perfectly for every type of trace we might see. Ideally, users could steer or bring their own prompts and structured outputs. For now, we started with a general-purpose prompt and summary schema that works well across most use cases — but enabling user-defined summarization is a potential future improvement.

- Zero-config — The Temporal workflows just run in the background. As you send traces to LLM Analytics, clustering will just work once there's enough data to sample from. No setup, no configuration needed.

- User steering — In the future, we'd love for users to define their own clustering configs, filter to specific subpopulations, and even kick off clustering runs on demand. For example, if you know you want to look at just your "refund request" traces, you could define a job for that. We're not there yet, but the architecture supports it.

Step 1: From JSON blobs to readable text

Traces are ingested into LLM Analytics as normal PostHog events. They have their own loose schema around special $ai_* properties — covering everything from generations and spans to sessions — but also the flexibility of general PostHog events, which means they generally work with any other PostHog feature out of the box.

However, this gives us a blob of JSON at the end of the day with some expected $ai_ properties, and even within each property the structure and format can vary wildly depending on the LLM provider, framework, or how users have instrumented their own agents.

So we need to figure out how to get from this bag of JSON to something a clustering algorithm can work with — we need numbers. And whenever you need numbers with LLMs, it often means you need embeddings. Our task is to figure out what embeddings to generate that will be useful downstream.

We can't just throw some massive JSON blob at an LLM and expect it to produce a great summary. It might be okay, but we can do better by putting ourselves in the shoes of our LLM: if I can create a general text representation where I myself can easily "read" a trace, then that'll also be a great input for summarization.

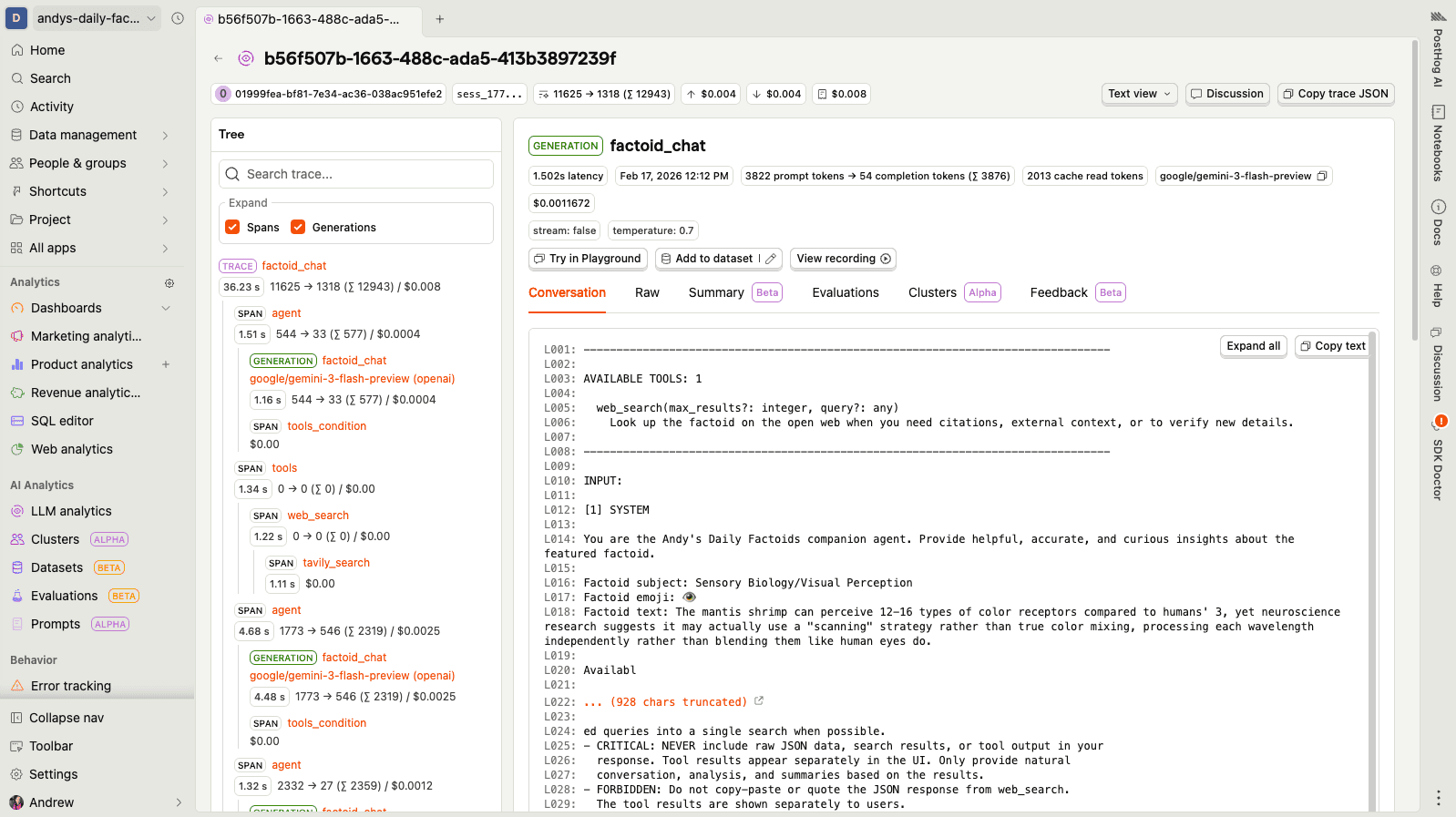

So we built a process that renders each trace as a clean, simple text representation — essentially an ASCII tree with line numbering. Here's what it looks like in the PostHog UI:

You can see the full text representation for this trace in this gist — it's a real example from one of my side projects (a daily factoids chatbot that got into a surprisingly deep conversation about mantis shrimp vision and digital signal processing).

The line numbering (L001:, L002:) is important — it gives the downstream summarization LLM a way to reference specific parts of the trace, which makes the structured output much more useful. You can see how this is generated in trace_formatter.py.

Handling huge traces

Some traces are just too big. We use uniform downsampling to shrink them — picking every Nth line from the body while preserving the header. The sampler notes what percentage of lines were kept, and the gaps in line numbers tell the LLM that content was omitted. Using the mantis shrimp trace from the gist, here's a snippet of what a downsampled version might look like:

Notice the [SAMPLED VIEW: ~40% of 136 lines shown] header and the jumps in line numbers (e.g., L051 → L059, L079 → L101). The LLM can still follow the conversation flow — the structure and key turns are preserved, just with less detail in between. This works well in practice because the same context often gets passed back and forth within each step of a trace. See the full implementation in message_formatter.py.

Step 2: Summarization

Now that we have a readable text representation, we can summarize it. We sample N traces per hour (cost management — we're not summarizing everything) and send each text representation to an LLM for structured summarization.

The key word there is structured. Rather than asking for a free-text summary, we ask for a specific schema:

See the actual implementation:

schema.py

We use GPT-4.1 nano for this — it's fast, cheap, and the structured output mode means we get reliable, parseable results every time. The line references back to the text representation are particularly useful: they let the summary stay grounded in the actual trace data rather than hallucinating. You can read the actual prompts we use: system_detailed.djt and user.djt. (If you have sensitive data in your traces, check out privacy mode which controls what gets sent.)

These summaries appear as $ai_trace_summary and $ai_generation_summary events in your project every hour. They also power the on-demand trace summarization feature you can use to quickly understand any individual trace or generation without reading through the full conversation.

Why structured output matters

Structured output is better than a raw summary for one critical reason: downstream embedding quality. When we embed a title + flow diagram + specific bullets with line references, we get a much higher signal representation than embedding a wall of free text. The LLM has already done the work of extracting what matters.

Why not RAG? We considered building a full RAG system — chunking traces, building indices, retrieving at query time. But the complexity of doing that well at PostHog's scale (billions of events across thousands of teams) made us reach for a simpler approach first. Summarization-first means each trace becomes a small, self-contained artifact that's easy to embed and cluster. We may still build RAG for features like natural language search, but for clustering, this works well.

Step 3: Embedding

Once we have summaries, we format them back into plain text — title, flow diagram, bullets, and notes concatenated together, with line numbers stripped to reduce noise — and embed them using OpenAI's text-embedding-3-large model, giving us a 3,072-dimensional vector for each summary.

Why embed the enriched summary instead of the raw trace? Because the summary lives in a higher-level semantic space. Raw traces contain a lot of noise — token counts, model versions, repeated system prompts. The summary captures the intent and flow, which is exactly what we want our clusters to be organized around.

So now, for each trace or generation, we have 3,072 numbers. Time for the fun part.

Step 4: Clustering

This is where we lean on more "old school" traditional ML techniques. There are still several areas where LLMs haven't eaten the world: recommender engines, clustering, time series modeling, tabular model building, and getting well-calibrated numbers for regression problems. For all of these, you're still better off equipping your agent with the tools to formulate and run traditional algorithms on the data, rather than asking it to do the calculations directly.

Dimensionality reduction

We can't just cluster the raw 3,072-dimensional vectors — the curse of dimensionality would make distances meaningless. So we first need to reduce dimensions while preserving the important structure.

We actually run UMAP twice, with different goals:

- 3072 → 100 dimensions for clustering:

min_dist=0.0packs similar points tightly together, which is what HDBSCAN wants. - 3072 → 2 dimensions for visualization:

min_dist=0.1keeps some visual separation so the scatter plot is readable.

HDBSCAN

For the actual clustering, we use HDBSCAN on the 100-D reduced embeddings:

See the actual implementation:

clustering.py

HDBSCAN has some nice properties for our use case:

- No need to pick k (number of clusters) in advance — it figures this out automatically based on density.

- Noise cluster — items that don't fit any cluster get assigned to cluster -1. These "outliers" can be interesting edge cases you might want to explore.

cluster_selection_method="eom"(Excess of Mass) tends to produce more granular, interpretable clusters compared to the "leaf" method.

After this step, every trace or generation has an integer cluster ID. But an integer doesn't tell you much — we need to make these meaningful.

Step 5: The labeling agent

Now we have clusters with integer IDs. Cluster 0 has 47 traces, cluster 1 has 23, cluster -1 (noise) has 8. Not exactly actionable.

This is where we bring AI back in — specifically, a LangGraph ReAct agent powered by GPT-5.2. Its job is to explore the clusters and come up with meaningful labels and descriptions. You can read the agent's system prompt in prompts.py.

The agent has access to 8 tools:

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

get_clusters_overview | High-level stats: cluster sizes, counts |

get_all_clusters_with_sample_titles | Quick scan of what's in each cluster |

get_cluster_trace_titles | All trace titles for a specific cluster |

get_trace_details | Full summary for a specific trace |

get_current_labels | See labels assigned so far |

set_cluster_label | Set name + description for one cluster |

bulk_set_labels | Set labels for multiple clusters at once |

finalize_labels | Signal that labeling is complete |

The agent follows a two-phase strategy:

See the actual implementation:

labeling_agent/

The two-phase approach is deliberate. If the agent only refined one cluster at a time and hit a token limit or error partway through, you'd end up with half your clusters unlabeled. Bulk-first ensures coverage, then refinement improves quality where it can.

Step 6: Orchestration with Temporal

All of this needs to run reliably across thousands of teams. We use Temporal workflows to orchestrate the pipeline.

A daily coordinator workflow discovers eligible teams (those with enough recent trace data), then spawns child workflows in batches — up to 4 concurrent workflows at a time to manage load:

See the actual implementation:

coordinator.py

The output of each child workflow is a set of $ai_trace_clusters and $ai_generation_clusters events. These are standard PostHog events, which means the clusters tab in the UI is just querying events like everything else in PostHog.

A concrete example

Here's what you're seeing in the demo:

- Scatter plot — Each dot is a trace, positioned using the 2-D UMAP coordinates. Colors represent cluster assignments. You can immediately see which groups of traces are similar and how they relate spatially.

- Cluster distribution — A bar chart showing how many traces landed in each cluster, with the agent-generated labels. This gives you a quick sense of what your users are actually doing.

- Drill-down — Click into any cluster to see the individual traces, their summaries, and the full details. This is where you find the patterns — maybe 40% of your traces are "user asking for refund status" and you didn't even know.

The noise cluster (labeled "Outliers") often contains the most interesting one-off traces — edge cases, unusual workflows, or bugs that don't fit any pattern. Pair this with evaluations (our LLM-as-a-judge feature) to automatically score the quality of generations within each cluster.

Try it now

If you're already using LLM Analytics in PostHog, clustering runs automatically — no configuration needed. Once you have enough trace data flowing in, clusters will appear in the clusters tab. If you're not using LLM Analytics yet, you can get started in minutes with SDKs for OpenAI, Anthropic, LangChain, Vercel AI, and many more.

- Clusters documentation — Setup guide and feature overview

- Custom properties — Attach your own metadata to traces for richer clustering

- Privacy mode — Control what trace data gets sent to PostHog

- Feedback — Leave feedback directly on the clusters docs page, email us at team-llm-analytics@posthog.com, or start a thread in the community

PostHog is an all-in-one developer platform for building successful products. We provide product analytics, web analytics, session replay, error tracking, feature flags, experiments, surveys, LLM analytics, data warehouse, CDP, and an AI product assistant to help debug your code, ship features faster, and keep all your usage and customer data in one stack.